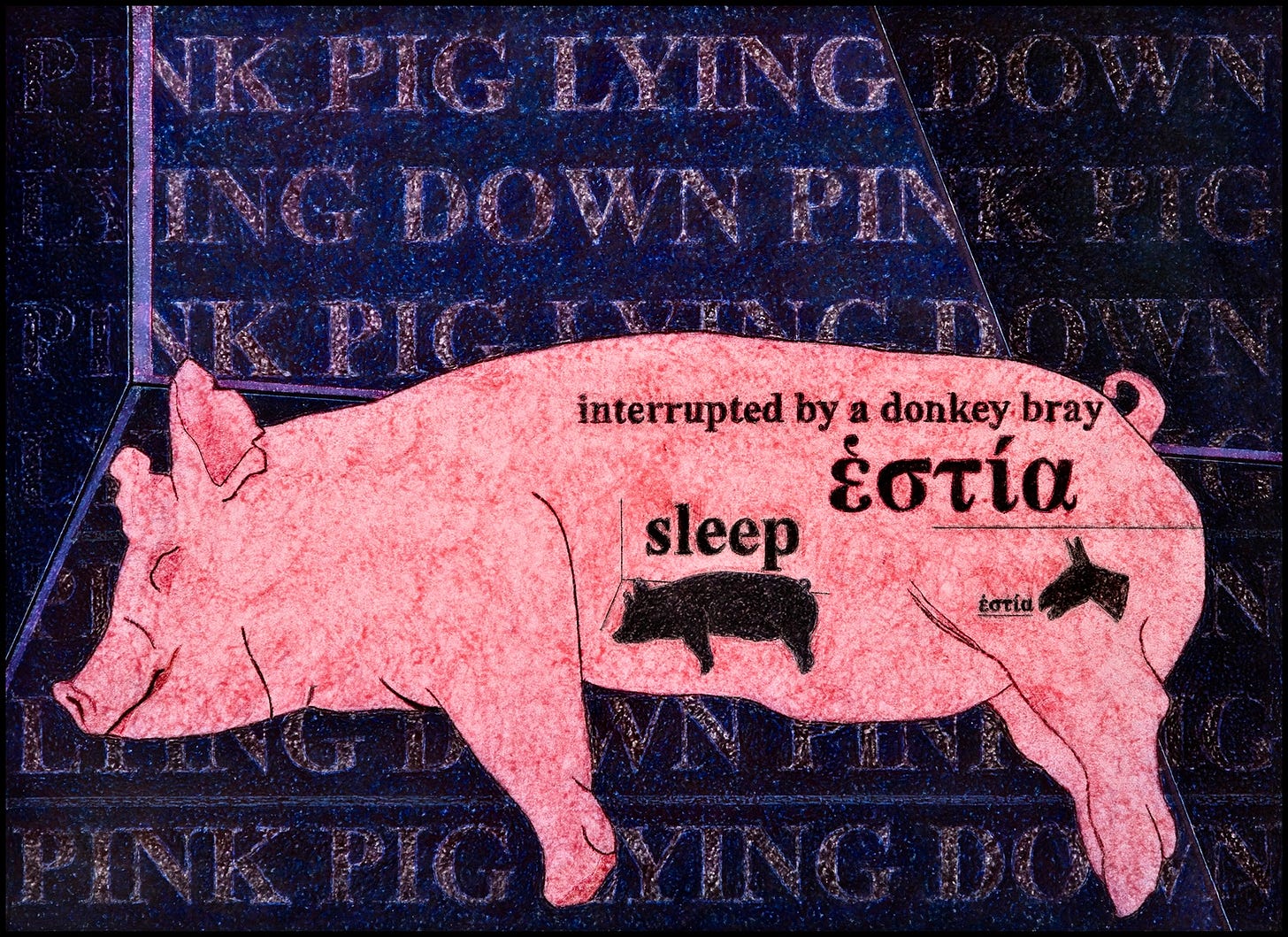

Hestia’s Repose

In Ancient Greek mythology, Priapus was the god of fertility. He ensured that vineyards survived frosts and that orchards bore fruit. Unfortunately, this also meant that he was forced into an unusually complex—and occasionally tortured—relationship with birds.

Biographically speaking, these difficulties began before he was born, when the goddess Hera cursed him with ugliness and sexual impotence. As an infant, Priapus was such an eyesore that his mother abandoned him in a pasture, safely out of sight from the other gods. Later he lived with winemakers, who were similarly disturbed by the repugnance of his face; however they were also impressed by the way its presence repelled the magpies that had been snacking on their grapes.

To capitalize on this effect, farmers began carving facsimiles of Priapus, which they would plant in their fields to scare away the birds. According to one account, this trend was responsible for establishing his reputation as a guardian of plants and, conversely, an enemy of birds. And yet, according to Horace, Priapus was not, in fact, sufficiently ugly to scare away the birds on his own. As a result, he took the fairly extreme measure of gluing a reed to his head. Each time he moved, the reed would flap around, startling any birds that might otherwise have chosen to perch on his permanently engorged member, which protruded from his body like a long, inviting branch.

Not only was her body motionless and warm but, in his mind, it was also extremely inviting

For obvious reasons, this protrusion was widely discussed among the ancient Greeks, who viewed it as further proof of his genius for fertility. For Priapus himself, on the other hand, it was an obvious consequence of Hera’s curse.

In Roman literature, the repercussions of this curse were serialized over centuries of stories and lewd poems. Like Elmer Fudd or Wile E. Coyote, the character in these myths was destined to chase an outcome he could never achieve, thereby encouraging a desperate appetite whose inevitable frustration allowed acts of foiled rape to be represented as episodes of comic relief in the same way that Looney Tunes would later transform acts of violent assault into an amusing spectacle for kids.

In one of Ovid’s stories, Priapus believed that he had finally gained a competitive edge over the prospect of another humiliating courtship when he stumbled on the goddess Hestia, dozing among a crowd of drunken party guests. Hestia shared her name with the Greek word for “hearth,” and, in the state that he found her, she resembled one very much: Not only was her body motionless and warm but, in his mind, it was also extremely inviting to a lonely stranger like himself: i.e. a stranger who had been thoroughly frozen by the protracted chill of an empty, loveless life.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, it’s reasonable to assume that his rustic childhood had given Priapus an unconventional—and uniquely agrarian—understanding of procreation, wherein stationary plants are pollinated by passing bees and dormant fields lie still beneath the blades of hungry plows. Either way, he chose to interpret Hestia’s slumber as an opportunity to ameliorate the pronounced—and extremely visible—state of sexual frustration that had been accruing since the days when he was still a fetus, napping in his mother’s womb.

And yet, for Priapus, impotence was a not a biological condition, but rather a conspiracy of fate, designed to obstruct his will. On this occasion, Hestia was woken by an observant donkey, allowing her to flee his grasp. On a separate occasion, another donkey managed to notify the gods that Priapus was attempting to violate a sleeping nymph. This time they intervened by transforming the object of his attentions into a tree—an exceedingly caustic gesture on their part, given that, as the god of fertility, his primary job was not only to protect plants from being ravaged by pests, but also to ensure that they successfully reproduced and bore fruit.

As an infant, Priapus was such an eyesore that his mother abandoned him in a pasture

He that would eat of love must eat it where it hangs, wrote Edna St. Vincent Millay in a poem from 1923, expressing a sentiment that Priapus would undoubtedly have understood quite well.

Though the branches bend like reeds, Though the ripe fruit splash in the grass or wrinkle on the tree, He that would eat of love may bear away with him Only what his belly can hold, Nothing in the apron, Nothing in the pockets. Never, never may the fruit be gathered from the bough And harvested in barrels. The winter of love is a cellar of empty bins, In an orchard soft with rot.

At the time she wrote this poem, Edna St. Vincent Millay was in the process of negotiating a wildly complex romantic life—a life which, incidentally, bore a certain resemblance to the one that was being lived by a contemporary of hers, several thousand miles away, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Ten years before, in the winter of 1913, the poet H.D. had already been engaged to Ezra Pound on two separate occasions and was about to marry someone else—a dissatisfying union which would eventually produce a stillborn child, a series of affairs and, ultimately, a divorce. Later she would enter into a lifelong partnership with a woman. Several years prior to that, however, when she was still flirting with the idea of becoming a traditional wife, she chose to write a poem about orchards—a poem which she fittingly titled “Priapus.”

Spare us from loveliness, she wrote in that poem, as though addressing the source of a longing that can never be quenched. Thou hast flayed us with thy blossoms.

Spare us the beauty Of fruit-trees!

Can you share what it is about the Priapus myth that inspired your drawing? I loved the drawing but as is the case with so many Greek/Roman myths, it's a curious, somewhat disturbing story.