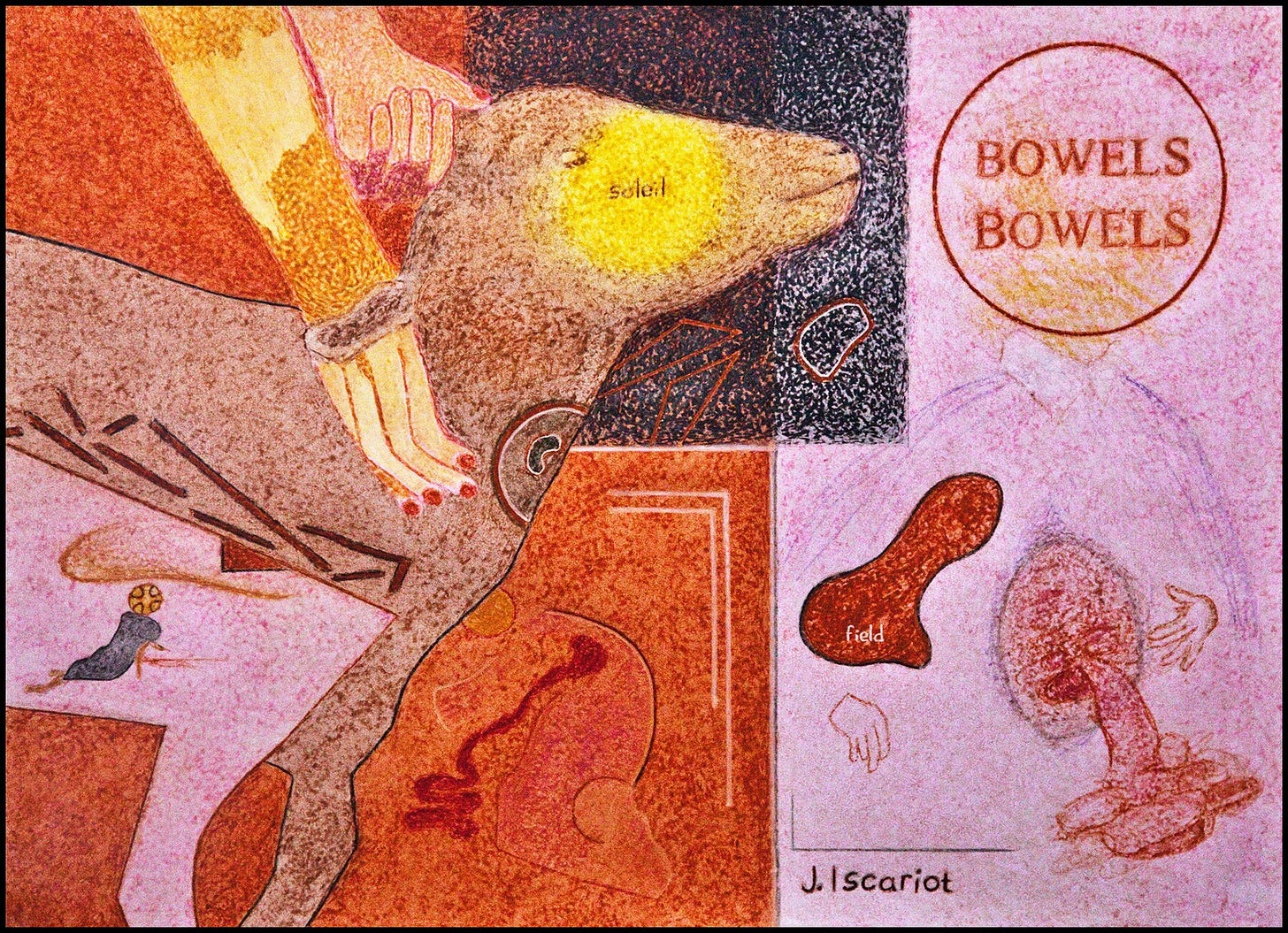

Several Variations on the Death of Judas Iscariot

Scribbled by Atticus Bergman using Crayola crayons | 22”x30” | 2019

Several Variations on the Death of Judas Iscariot

For centuries, theologians have bickered about a puzzling sequence of events that took place between Jesus Christ and his traitorous disciple, Judas Iscariot. By now it’s all very murky. However, what we do know is that, when he was about 30 years old, Jesus Christ was baptized in a river—a refreshing experience which not only invigorated him for the afternoon, but also inspired him to spend the next few years earnestly advising everyone he met that they should do the same. Unfortunately, this interval of promulgation came to an end after Christ was abruptly hauled into court, convicted of almost half a dozen crimes, and publicly executed with such panache that the whole affair is still remembered to this day.

According to several people who were present at the time, the sudden downfall of Jesus Christ was most likely related—in one way or another—to an outrageously meaningful kiss that Judas planted on the cheek of his master. Unsurprisingly, this gesture sparked a flurry of rumors among the other disciples, who later deduced that it must have been a clandestine signal—or, at the very least, an ambiguous symbol. Paradoxically, the treachery of this symbol lay in the extravagant purity of its affection, whose telling combination of deference and respect effectively announced the presence of the King of the Jews, thereby allowing the local authorities to recognize the suspect that they had been ordered to arrest. Of course, this theory completely ignores the fact that, by then, the identity of Christ was not exactly a secret, especially given his notorious habit of calling attention to himself by, among other things, climbing to the top of a mountain, illuminating himself in sheathes of luminescence, and becoming so radiant with glory that “his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became bright as light.”

One common interpretation holds that Judas Iscariot was damned to hell for his decision to cooperate with the government—an act of retaliation which, all things considered, probably had more to do with the status of the man Judas betrayed than it did with the betrayal itself. After all, by unmasking the truth of Christ’s preeminent position, Judas was merely doing what Jesus himself had been doing for years. Furthermore, Jesus had already announced his own betrayal during an especially boozy dinner the night before—a revelation which he chose to stage by performing an elaborate party trick in which he employed a piece of bread to demonstrate that his father had chosen Judas Iscariot as the traitor who would help him fulfill the prophesy of Christ’s sensational demise. By the end of the night, the implications were clear: God had a plan for his son. And that plan did not involve him dying demurely in his sleep.

“Since they did not want to exhume the body again, a twist of a knife did the trick. The corpse was decapitated and the horrible face, running with scars and pus, again faced the victors.”

Needless to say, Judas was horrified to learn that he had been appointed to betray his master. As such, it makes sense to understand his kiss as a poignant gesture of goodbye to a departing friend—an act of startling intimacy, whose tenderness joined them together in a private conspiracy to co-produce the ensuing theater of Christ’s ascension. In the meantime, the other disciples were excluded from this pact and cruelly relegated to more prosaic, secretarial tasks, such as assisting in the creation of various informational pamphlets, which would later be compiled into a scrapbook of memories that chronicled the life and deeds of their departed master.

In 1944, the uncanny bond between Jesus and Judas inspired the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges to write a short story exploring the notion that, philosophically speaking, the two men were complex reflections of each other. As articulated by this story, the unusual symmetry that defined their relationship made their relative positions nearly impossible to untangle, so that it was actually quite probable that Jesus, rather than Judas, was the unwitting instrument in God’s plan, and that Judas was the real Son of God. This theory can easily be corroborated by a few points of Biblical reasoning. For instance, if God were serious about following the logic of incarnation—a logic which required that his son’s humanity be affirmed by vivid displays of suffering, fallibility, and death—then it makes sense that his son would also be vulnerable to sin and, ultimately, to damnation itself. As Borges put it: “To limit His suffering to the agony of one afternoon on the cross is blasphemous. To claim that He was man, and yet was incapable of sin, is to fall into contradiction.”

In other words, the authenticity of Christ’s humanity paled in comparison to that of the man who betrayed him. To back this up, Borges placed a footnote in the text, citing the ideas of Antônio Conselheiro—the Brazilian minister whose heretical teachings were so compelling to his followers, and disturbing to his enemies, that they provoked the deadliest civil war in the history of Brazil. Among other things, Conselheiro was a zealous proponent of Sebastianism, which codified the conviction that King Sebastião of Portugal would return, presumably from wherever he had been hiding for the previous three hundred years, in order to reclaim the Portuguese throne and unite the planet under his benevolent rule, in preparation for the second coming of Christ.

The origins of this idea began in 1578 when Portugal’s rash, new king decided that he wanted to personally vanquish the army of Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik. At the time, King Sebastião was 24 years old and vaguely aware that, given his general lack of character, he was unlikely to earn very much respect unless he did something profoundly unwise. In this spirit, he set out to conquer the infidels and, in a poetic flourish, also forbade his troops from taking any action against the opposing soldiers unless they received an order directly from him. Unfortunately, in the heat of battle, he forgot to give this order, which meant that a significant portion of his army stood motionless while the moorish cavalry mowed them down like so many farmers, harvesting a field of wheat. To make matters worse, Sebastião had invited most of the Portuguese nobility to be in attendance at the battle, so that they could witness his transformation into a national hero. Instead they were slaughtered en masse or captured and sold into slavery. Then, in the midst of this carnage, the young king was absorbed into a crowd of heavily armed enemies, at which point he mysteriously vanished and was never seen again.

“To limit His suffering to the agony of one afternoon on the cross is blasphemous. To claim that He was man, and yet was incapable of sin, is to fall into contradiction.”

If the enigmatic nature of King Sebastião’s disappearance from public life allowed his citizens to fantasize about his possible return, then the last moments of Judas Iscariot’s life were equally confusing and, in their own way, similarly impactful. Indeed, the Bible’s accounts of Iscariot’s death are so muddled that their contradictions were responsible for convincing C. S. Lewis to permanently abandon the idea of Biblical infallibility. That being said, his death does seem to have involved a field of some sort. One version suggests that he hung himself in this field. Another version claims that he suddenly became ill and knelt down in the field, at which point his belly split open and his bowels spilled into the dirt. According to the Gospel of Nicodemus, his last few hours involved a sarcastic comment made by his wife while she was in the kitchen, roasting a chicken on a spit.

In contrast to this, Antônio Conselheiro’s death was affirmed unequivocally, in gruesome detail. Even so, its precise cause remains ambiguous. As far as Euclides da Cunha was concerned, the man died of a broken heart after seeing his churches destroyed by the Brazilian military. Meanwhile, the man who found his body claimed that he died of acute diarrhea—a statement which apparently made a room full of government officials chuckle with spontaneous mirth when they heard the news. Either way, the Brazilian republic was determined to ensure that any rumors produced by this indeterminacy would not follow the same course as those provoked by the unresolved denouement of King Sebãstiao. In the words of da Cunha: “Since they did not want to exhume the body again, a twist of a knife did the trick. The corpse was decapitated and the horrible face, running with scars and pus, again faced the victors. Afterward they took it to the coast, where it was greeted by crowds dancing in the streets in impromptu carnival celebrations. Let science have the last words. There, in plain sight, was the evidence of crime and madness.”