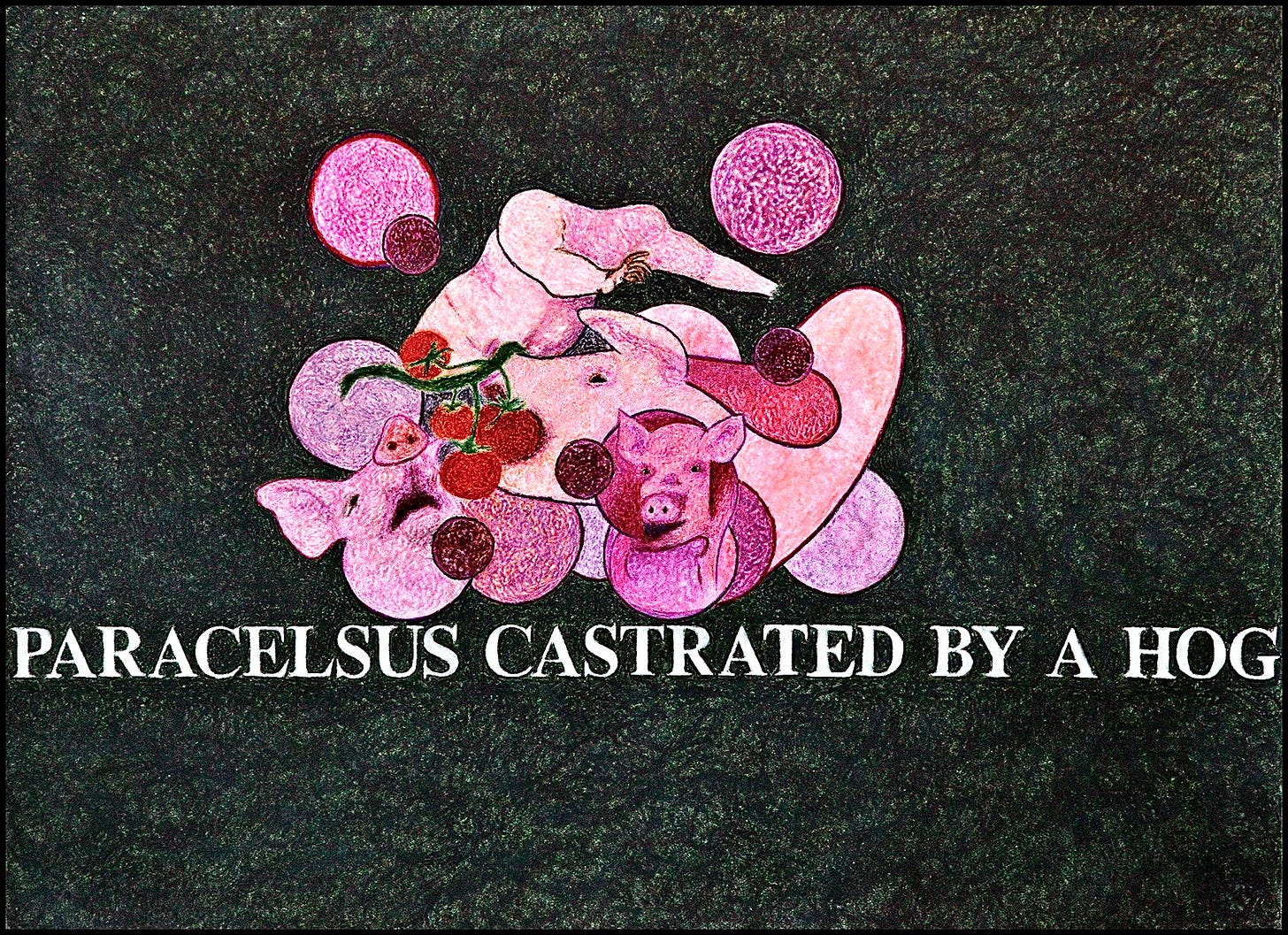

Paracelsus Castrated by a Hog

Scribbled by Atticus Bergman using Crayola crayons | 22”x30” | 2020

Paracelsus Castrated by a Hog

After almost five centuries of historical analysis, there’s still a certain amount of confusion surrounding the question of what, exactly, happened to the testicles of Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim—the itinerant physician who was better known as Paracelsus. According to one legend, his gonads were plucked from his body by an insolent goose while he was herding poultry as a child. A few years after Paracelsus died, Thomas Erastus maintained that soldiers had drunkenly performed an operation on him in a roadside tavern. A third story claims that it was not soldiers who castrated him, but rather his own father. Meanwhile, in a parenthetical statement that he inserted partway through the byzantine text of The Recognitions, William Gaddis managed to crisply ratify a fourth theory, which asserts that a mischievous pig chewed them off when Paracelsus was still a boy—a theory whose more dramatic corollary insists that it was not a farm animal that unmanned him, but in fact a wild boar.

As far as contemporary historians are concerned, most of this speculation was engendered by the simple fact that Paracelsus was never married. In the minds of those who knew him, this implied some sort of physical deficiency, which they were more than happy to explain in great detail by adhering to the general logic of inference and deduction. That being said, it’s also quite possible that the man’s inability to find love was related to his habit of behaving, at all times, in an intensely disagreeable fashion.

In 1525, Paracelsus made such a nuisance of himself that the government of Salzburg threatened him with public execution, forcing him to leave town rather abruptly, without any clothes. Later he made similar exits from Baden, Tübingen, and Nuremberg after antagonizing his fellow doctors, who, in his words, were ignorant butchers that deliberately “cripple and maim, sometimes strangling or even killing people, so that their own profit can be increased and not impeded.”

While practicing in Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, Paracelsus was forced to flee on short notice after accidentally murdering some of his influential patients—a standard occupational hazard of the time. However, in Strasbourg, the circumstances of his departure were slightly more humiliating: During a public debate, one of his colleagues maliciously exposed his rudimentary knowledge of human anatomy—a subject which he had never pretended to know that much about, given its relative unimportance in comparison with the deeper mysteries of the human soul.

Paracelsus “lived like a pig, looked like a coachman and took pleasure in the company of the loosest and lowest mob.”

Following an incident that transpired in Innsbruck, Paracelsus wrote that “I was dispatched with contempt and was forced to clear out.” After that, he traveled to Sterzing, where he attempted to inoculate the local residents by feeding them bread smeared with feces that had been collected from victims of the bubonic plague. Suffice it to say, his patients did not appreciate this innovation.

In Basel, Paracelsus briefly held a position as a professor of medicine, which he employed to ridicule the credentials of his colleagues, calling them “a misbegotten crew of approved asses.” More importantly, he also took issue with their reliance on outdated texts from antiquity. “Let me tell you this,” he wrote in 1529, “every little hair on my neck knows more than you and all your scribes, and my shoe buckles are more learned than your Galen and Avicenna, and my beard has more experience than all your high colleges.”

To prove this point, Paracelsus publicly burned the books of several canonical doctors in a bonfire that took place on the 24th of June, 1527. Around the same time, he invited his fellow professors to attend a lecture in which he promised to reveal some of the medical secrets that their boundless imbecility had made them overlook. After they had dutifully assembled in his classroom, he presented the group with a dish of human shit, which he heated until it began to steam. Then he shouted insults at them as they scrambled for the door. Shortly thereafter a warrant was issued for his arrest, at which point he escaped town in the middle of the night.

Because of his disdain for institutional authority, Paracelsus was often compared to Martin Luther—a comparison which Paracelsus violently refused. According to him, there was no substantial difference between the Catholic Church and the man who wished to reform it. Or, as he put it: Luther and the pope were nothing more than “two whores debating chastity.” Even so, there’s no question about the revolutionary spirit with which Paracelsus promoted his belief that “the art of medicine cannot be inherited, nor can it be copied from books; it must be digested many times and many times spat out; one must always re-chew it and knead it thoroughly, and one must be alert while learning it; one must not doze like peasants turning over pears in the sun.”

From the perspective of modern medicine, the legacy of Paracelsus is hard to define. Instead of advancing treatments through iterative, technical development, his rambunctious spirit forced the sphere of clinical epistemology to accommodate the presence of a mutinous insurgent, thereby opening a new space of thought, which was later filled by the emergence of disciplines like toxicology and advanced pharmaceutics. In large part, this expansion was driven by the way that Paracelsus was able to reinterpret the art of alchemical transformation, which, for him, was not a process of combination and transcendence, but rather a practice of systemizing, purifying, and adjusting the natural order of the world. “The art of prescribing medicines,” he wrote, “consists in extracting and not in compounding. It consists in the discovery of that which is concealed in things.”

To explain the power and scope of alchemical thought, Paracelsus argued that “we do not have to eat hair to grow a beard,” by which he meant that there is a profound capacity for the provisional structures of the world to be refashioned according to a logic that is not always as straightforward as it might seem. For Paracelsus, this meant isolating the surprising pathways through which knowledge could be separated from confusion. As an example, he cited the digestion of pigs. More specifically, he cited the fact that pigs are content to snack on human feces, whereas humans are not usually inclined to snack on pig feces—a contrast which implies that the digestive system of pigs is more sensitive to the distinction between nutrition and waste. In situations where humans see nothing but undifferentiated excrement, pigs are able to discern the presence of something valuable, which their bodies extract in the same way that a human might remove a fruit from its husk.

As he put it: Luther and the pope were nothing more than “two whores debating chastity.”

Unfortunately, it’s no secret that Paracelsus had a complicated history when it came to the subject of pigs. Aside from the specific hog that may or may not have taken an unwelcome bite from one of his most tender and available organs, those who were familiar with the doctor’s personality had a tendency to remark on his uncanny affinity with the behavior of the porcine species. According to Johann Georg Zimmerman, Paracelsus “lived like a pig, looked like a coachman and took pleasure in the company of the loosest and lowest mob.” Similarly, Johannes Oporinus remarked that Paracelsus once “challenged an inn full of peasants to drink with him and drank them under the table, now and then putting his finger in his mouth like a swine”—a statement which Oporinus went on to elaborate in a different passage, where he declared that “apart from his miraculous and fortunate cures in all kinds of sickness, I have noticed in him neither scholarship nor piety of any kind. It makes me wonder to see all the publications which, they say, were written by him or left by him but which I would not have dreamed of ascribing to him. The two years I passed in his company he spent in drinking and gluttony, day and night. He could not be found sober, an hour or two together, in particular after his departure from Basel.”

While it may be true that there are just as many stories about the death of Paracelsus as there are about his castration, nearly all of them seem to emphasize his fondness for spending time in pubs. One story has him falling down a set of stairs after drinking so much that he spontaneously lost his sight. Another story alleges that he died in a drunken brawl. A third story claims that his enemies hired assassins to beat him to death in an alleyway. A fourth story suggests that those same enemies actually killed him by sprinkling powdered glass in his beer. Another variation maintains that they lured him to a cliff with a promise of free booze and then threw him over the edge. Regardless of the precise circumstances that led to his ultimate demise, Paracelsus appears to have spent his last few days on a cot in a tavern, where he requested that his body be cut into pieces and buried in manure. After researching the matter thoroughly, one of his biographers was able to confirm that, when these pieces were exhumed thirty years later, the pieces had somehow managed to grow back together, sparking rumors that the doctor’s alchemical knowledge had allowed him to experiment with his own immortality.

In the time since, the bones of Paracelsus have led an adventurous existence whose drama matches that of his life. They’ve been moved, misplaced, studied, stolen, and sealed in an iron box. And yet, to this day, modern analysis remains uncertain about the question of whether or not he was, in fact, castrated while he was alive. What is known, however, is that among his remedies for the sexual frustrations of unmarried men was a suggestion that bachelors remove their testicles with a quick slash of a knife—a treatment which he perceived as being both easy and self-evident, given the convenience with which the male reproductive organs dangle on the outside of the body, like apples on a tree.

In other words, if Paracelsus actually was castrated, there is a distinct possibility that he did the deed himself. Fortunately, as a renowned physician, he was supremely qualified to address the resulting wound. Indeed, when it came to problems with the testicles, Paracelsus recommended a potion made from the bulbs of orchids. On the other hand, when it came to the larger challenge of love, Paracelsus prescribed the dismembered private parts of turtle doves or sparrows, thereby presupposing an economy of genitalia in which testicles could be exchanged across species so that one creature’s loss—however traumatic—could always be transformed into another’s path to health.