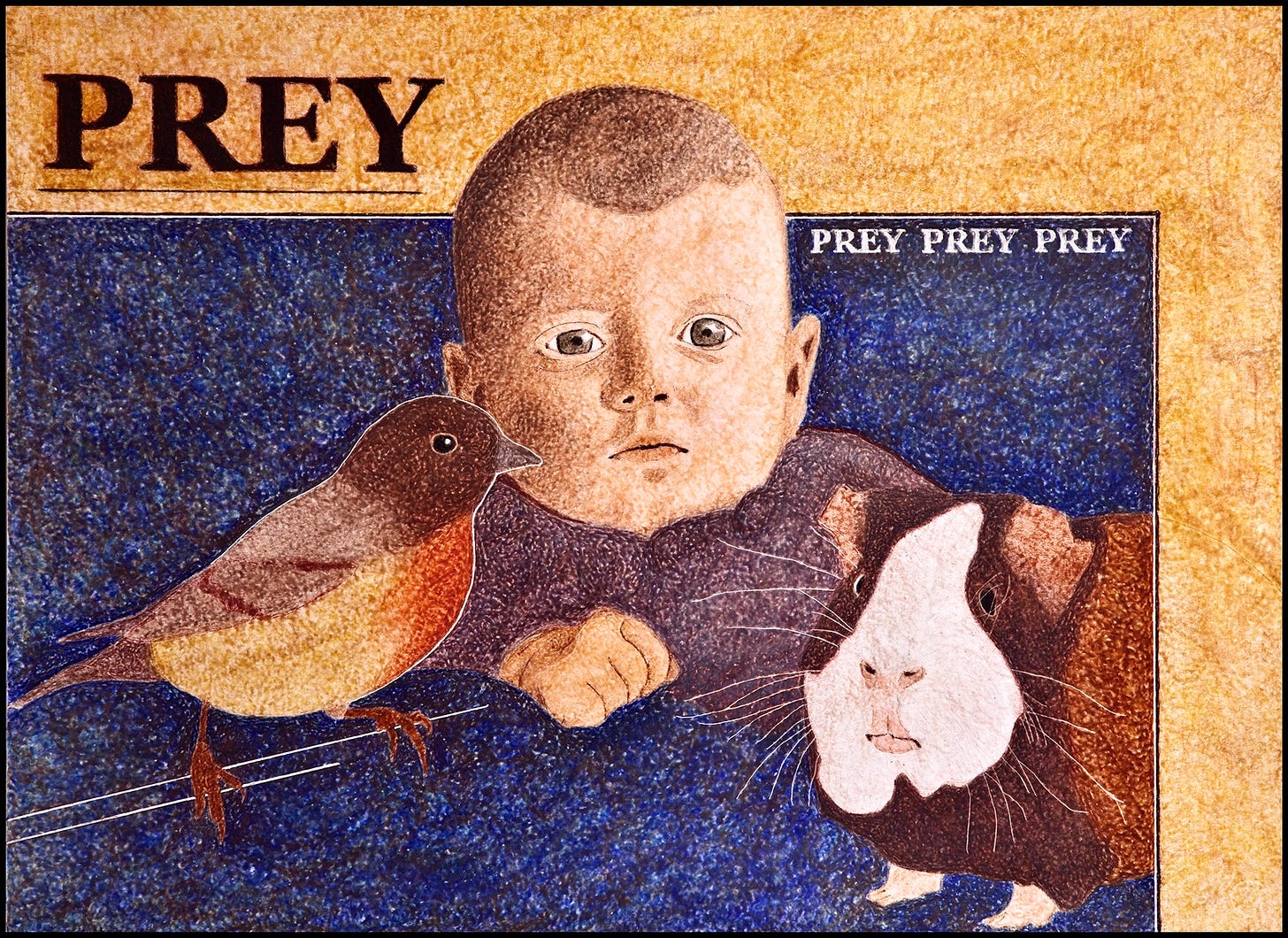

Prey

Scribbled by Atticus Bergman using Crayola crayons | 22”x30” | 2022

Prey

“A man is born gentle and weak; at his death he is hard and stiff,” wrote Lao Tzu in a ten line aphorism which went on to associate suppleness with vitality and brittleness with destruction, suggesting that the symbolism of the natural world can be translated into political insights about the strategic exercise of strength.

Broadly speaking, power is often considered to be a fungible resource that can be gained, lost, squandered, and hoarded. And yet, like any resource, its advantages cannot necessarily be claimed by the individuals who are most subject to its influence. For them, power exists as a distant abstraction, distributed geographically like the stars in the sky. In certain places, those stars may be bright and dense. However, as a spectacle, their radiance merely calcifies the impotence of their audience, who can do little more than watch them twinkle from afar.

For defenseless herbivores like guinea pigs, the absence of power has evolved into an existential condition so intense that it has strangled their ability to survive in the wild. After several millennia of domesticity, the safety of the species depends on their confinement—meaning that, in their cosmos, weakness is a nonnegotiable position whose ramifications must be managed and accepted, rather than negotiated or reversed.

One way that guinea pigs cope with their own helplessness is by freezing in the presence of threats. In these moments, their body stiffens and their heart rate slows. From the perspective of a military tactician like Lao Tzu, this reaction could, in theory, be interpreted as a willful forfeiture of aggression—or, at the very least, as a strategic form of disguise. And yet, from a physiological perspective, these moments are not voluntary at all. Instead, they evoke Lao Tzu’s warnings about the profound entanglement of stiffness and death. Meanwhile, the diminished vitality of their organs suggests the wisdom of retreating from life altogether. After all, certain lives, if lead with the audacity of the brave, can only end badly.

“We are unconsciously cultivating our violence by disavowing our helplessness”

Studies of serotonin in anxious rodents indicate that freezing behavior can be manipulated by specific pharmaceuticals which effect their susceptibility to fear. When the animals are relaxed by serotonin inhibitors, they freeze less often. Similarly, when they are given anti-psychotic medication, they become more sensitive to the concept of danger, thereby increasing the rate at which they freeze.

In psychoanalytic terms, this implies that freezing is a defense against internal anxiety rather than a simple response to external threats. In humans, psychotic states protect individuals from the experience of vulnerability by loosening their ties to reality—a dimension of life that, when truthfully encountered, tends to justify the emotions of fear and distress it typically provokes. Within the scope of quotidian psychopathology, similar transactions occur when reactions of antagonism or joy are sustained by what analysts like Melanie Klein have termed the “manic defenses.” In these situations, outward stimulation is mobilized against internal knowledge, so that acts of erotic entanglement, frivolous amusement, or interpersonal aggression occlude the possibility of gaining meaningful insight into the question of where one’s frailties truly lie.

“Psychoanalysis, whatever else it is, is a story about how we protect ourselves from our helplessness, from our incapacities; from our knowledge of these things and from our experience of them,” wrote Adam Phillips in 2010. In his clinical practice, Phillips’ specialty is children, whose psychopathologies are often related to their vulnerability—or, at any rate, to the manner in which that vulnerability is utilized by others.

Like furniture in the hands of discount movers, small children are seemingly designed to be mishandled by those that deliver them. As such, they often reveal the mechanics of everyday sadism—an emotional tool that happens to be extremely convenient for anyone who prefers the security of self-empowerment over the anxiety of self-doubt.

Certain lives, if lead with the audacity of the brave, can only end badly

By noticing the conspicuous vulnerability of children—and then absorbing it into the venerable tradition of sadistic self-improvement—adults are able to locate the presence of weakness on a social map, thereby disguising its concurrence in themselves. This form of aggressive dissemblance inspired Adam Phillips to claim that “we are unconsciously cultivating our violence by disavowing our helplessness,” a conclusion he derived from Freud’s conviction that the “original helplessness of human beings” is the “primal source of all moral motives.”

Even so, when it comes to weaponizing vulnerability, sadism is only one tool among many. In the same way that sadists leverage the weakness of others to elevate themselves, masochists leverage their own fragility to exert control over the precise manner in which they are objectified and abused. In the natural world, this technique is especially useful for creatures like mushrooms, whose culture of reproduction relies on extravagant feats of sexual perversion. Truffles, in particular, face a confounding predicament. Not only are they legless and unable to move, but they also develop underground, where they are invisible to pollinating insects and unaffected by the movement of the wind. Consequently they have evolved to seduce the olfactory palette of certain mammals, cultivating a sensual musk which makes them more likely to be sniffed out and devoured. In other words, they are one of the depraved beings of the world that actually invites being eaten. Instead of directing their sexuality towards each other, truffles court the attention of their predators, who grind them up, digest them, and then propagate their spores in the form of waste.

We are shelves, we are Tables, we are meek, We are edible,

wrote Sylvia Plath in a poem about mushrooms, briskly relating the concepts of immobility and desire, before ending her train of thought with a reference to Christ’s Sermon on the Mount.

By concluding her poem with an assertion that the edible and meek shall “by morning / inherit the earth,” Plath echoes the language of the Bible as well as that of Lao Tzu, who chose to conclude his own discourse on softness by remarking that “the hard and stiff will be broken,” whereas “the soft and weak will endure.” And yet, Plath’s complex knowledge of weakness was more honestly expressed in the text of her only play: “I am helpless as the sea at the end of her string,” she wrote at one point in Three Women.

Restless and useless. I, too, create corpses.