Tatiana de Schlözer

In one of history’s routine humiliations, Tatiana de Schlözer was quickly forgotten after her death in 1922. Since then, a century has transpired, adding decades of further neglect to the evaporating contours of her life. Today, in the rare moments when she is remembered at all, it is not for the quality of her character or the magnitude of her accomplishments, but rather for a position she once inhabited—a conjugal position, to be precise, whose attendant duties placed her in extreme proximity to one of Russia’s most ambitious men.

That man was Alexander Scriabin who, by the end of his life, was almost as famous for his romantic temperament as he was for the music he composed. In 1902, this aspect of his personality allowed him to fall madly in love with Tatiana—an event which was only slightly hindered by the fact that, at the time, he was already married to someone else. Meanwhile, in his professional life, the intensity of his creative process encouraged his passion for music to evolve into a messianic project that was, quite literally, world-historical in scope.

After leaving his wife to elope with Tatiana, Scriabin was unable to obtain a divorce. Fortunately this wasn’t especially important for the happy couple; or at least it wasn’t until 1907, when the ambiguous legality of their relationship was leaked to the American press shortly after they arrived in New York, forcing them to cancel their trip and flee the wrath of a nation that was fully prepared to defend itself—by any means necessary—against their adulterous criminality.

“Her favorite theme of conversation is her warts, which have led to the most improbable adventures.”

Even so, Tatiana appeared to embrace the condition of adjacency that emerged from her proximity to Scriabin—and, by extension, from her proximity to his wife. By her own account, she first discovered Scriabin’s music when she was fourteen years old. A few years later, she attended a performance of his third sonata, which she described as the most important experience of her life. When she finally came to know the man himself, she was already so inspired by his work that she abandoned her own career and embarked on a project that she viewed as more ambitious and fulfilling: attuning herself to the complexity of her partner’s art.

In this respect, Scriabin was more than happy to affirm her priorities, which—as it happened—were also his own. “My enchantment,” he exclaimed to Tatiana in 1906, “I bow down before the greatness of the feeling which you grant to him who dwells in me.”

Four years after he wrote those words, Scriabin returned to the same theme in a poem about the meaning of his fourth sonata. Paradoxically, the fact that the last two lines of the poem are about his music—and not Tatiana—only amplifies their relevance to the asymmetries that defined her life: “I drink you in—a luminous sea! / Light of my own self—I engulf you.”

In my capricious Play I forget you, momentarily In the vortex which carries me away I move away from your rays In the intoxication of desire You disappear—a distant goal!

Unsurprisingly, Scriabin’s earliest fiancée had mixed feelings about surrendering her life to this kind of adjacency. For most of the early 1890s, Natalya Sekerina and Alexander Scriabin were passionately in love with each other. However Natalya’s mother disapproved of the match and, eventually, her daughter married someone else. “What sort of wife would I be for a genius?” Sekerina explained many years later, after Scriabin had died. “I think that my subconscious showed me the right path at that time.”

In the summer of 1893, when this future had not yet come to pass, Scriabin wrote a series of letters to Natalya which described, in vivid detail, a punishing treatment that he was undertaking at a sanatorium in Samara. Each patient was required to imbibe as much kumiss as possible—a drink made from fermented mare’s milk that, according to Scriabin, was brewed by Kirghiz natives to circumvent a ban on alcoholic spirits. As such, the institute’s daily program had rapidly plunged the clinic into a delirious cycle of prescribed drunkenness, punctuated by involuntary naps.

Unfortunately, this situation made it impossible for the composer to work; however it did seem to enliven the observations that filled his letters. Over the course of his stay, one woman in particular caught his attention. As he put it to Natalya: “Her face has the expression of a question mark with a very prominent nose, on the end of which fate has willed two warts. Unheeding destiny has furnished one of them with three red hairs. The lady places all her moral strength in these hairs and therefore never trims them.”

This woman is bad, spiteful, and irritable. Her favorite theme of conversation is her warts, which have led to the most improbable adventures.

Here is her favorite episode: Moved to tears at some group for reading sentimental poetry, she took out her handkerchief to blow her nose. She accidentally got one of her warts and let out a screech or made some sort of odd sound which broke the deep silence and made her look as if she were terribly ill-mannered. Now since good breeding is the highest of virtues to this lady, from that day on she set about destroying the warts. Every day she cauterized them. This did not stop the growing. It only changed their color.

She is very famous in meteorological and medical circles, and she even plays an important role among residents here. Her warts forecast the weather by turning dark blue and brown in rain and cold, and bright red in clear weather and heat. The doctors prescribed kumiss for her, and she is to drink it until she becomes beautiful!

One evening, when he was about seven or eight years old, Scriabin’s aunt read him Gogol’s story about a civil servant who discovers that his nose has gone missing from his face—a humiliation which only worsens when the poor man is forced to watch the nose ride past him on a stately horse, wearing the uniform of a Russian high official. Given the specificity of this formative experience, it’s only natural that, at the age of 21, Scriabin would be unusually attuned to the drama of nasal physiognomy. And yet, he wasn’t the only resident of the sanatorium to be inspired by the woman’s warts. Over the course of four separate sittings, one of his fellow patients made a painting of her nose—and all its adornments—which was so arresting that Scriabin felt compelled to describe it, at great length, in one of his letters to Natalya:

“The portrait was magnificent! True, the face was rather hidden and didn’t look like her, but all the details and embellishments stood out in relief and struck the eye instantly. First of all there were two bright purple warts looking like balls of fire, and on one of them he had painted three huge red hairs, and on the other sat a fly. Her birthmark over her left eye looked like an ink blot with whiskers tough enough for a sergeant-major. There is no human language with sufficient vocabulary to express the fury of the lady when she saw how scandalously she had been painted. She grabbed the first knife she saw and poked the eyes of her own portrait and cut it, and threw it over the terrace. There, some street urchins picked it up and added insult to injury. They took a dead toad and tied it to the picture. Finally, they fastened it to a post.”

“Her warts forecast the weather by turning dark blue and brown in rain and cold, and bright red in clear weather and heat.”

The reason why Scriabin had been exiled to a remote sanatorium in the first place was because he was having problems with his hand. According to his aunt, these problems began when he was unexpectedly run over by a horse while crossing the street. As he grew older, this injury was strained by overuse until it not only affected his ability to play the piano, but also influenced the style of his compositions.

For awhile, the influence of this injury was mostly apparent in the technical demands of the music he wrote for piano, which increasingly relied on the virtuosity of the left hand, rather than the right. However, it also shaped the tonal architecture of his pieces, especially as its ancillary effects were absorbed into a mystical philosophy that, for Scriabin, explained how the physical textures of the world could be dematerialized and transformed into sound.

By following this train of thought to its logical conclusion, Scriabin came to believe that many of life’s corrupting influences could be purified by synthesizing the complexity of the world into a ritual of symphonic apotheosis. In a way, this idea could already be seen in a letter that he wrote to Natalya’s sister in 1892, where Scriabin mentions a text by Ernest Renan that, in turn, refers to a grand, metaphysical unity “in which every individuality, down to that of the last insect, will have had its part [and] all individuality meets again as if in the distant sound of an immense concert.”

Once again, the stories of Gogol are strangely helpful—especially when it comes to imagining what kind of concert could, in theory, have been formed by the unique constellation of features that were on display in the painting of the woman at the clinic, with its nose and its warts and its colors and its fly. Unfortunately, Gogol doesn’t have much to say about warts or insects; however, in a short story called “The Lost Letter,” he does describe a group of musicians who “banged on their cheeks as if they were drums, and blew with their noses as if they were French horns.”

More recently, scientists have determined that houseflies sing in the key of F. This fact stems from the frequency with which they flap their wings; furthermore, it appears to ratify Aristotle’s claim that insects “have no voice and no language, though they can emit sound by internal air or wind.” Several decades before Aristotle, Aristophanes offered some more pointed commentary about the buzzing of flies when he described an imaginary conversation between Socrates and one of his pupils. In this conversation, Socrates insists that, contrary to popular belief, an insect does not sing through its proboscis. Instead, it inhales parcels of air through its nose and then pushes them through its gut, where they gather enough force to activate the resonant qualities of the anus—an organ which Socrates poetically describes as being “distended like a trumpet.”

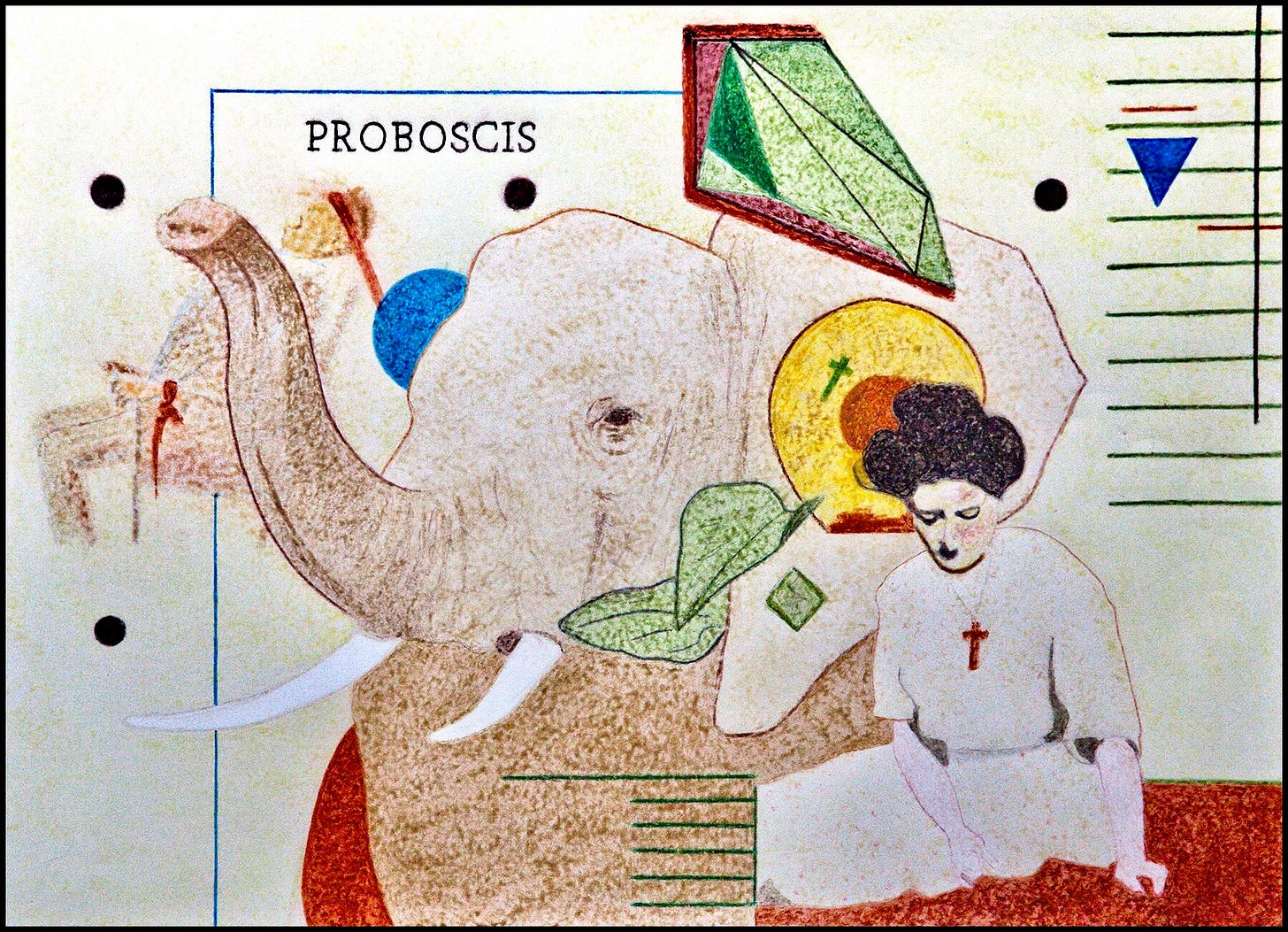

In contrast to the satirical arguments of Aristophanes, an article from the March, 1880 edition of The American Naturalist asserts that, over the course of history, it is not the anus of the housefly, but in fact its proboscis which “has attracted much attention and been the subject of much misapprehension.” Incidentally, this statement could also be applied to elephants, whose facial anatomy mimics the housefly on such a grand scale that biologists have classified them under the order Proboscidea.

In 1847, Robert Harrison gave a lecture about elephant anatomy which was subsequently published in the third volume of the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. “For the prehension of food the proboscis is indispensable to his existence,” he exclaims at the beginning of a rhapsodic monologue about the organ that describes, among other things, how the elephant’s trunk “enables him to remain in deep water, his whole body immersed and concealed from view, except the point of the proboscis, which appears just over the surface.”

In retrospect, it’s obvious that Harrison was overwhelmed by the delicacy and sophistication with which the elephant can manipulate its trunk to accomplish ordinary tasks. Consequently there is an unexpected tenderness, as well as a profound sense of intimacy, in his explanation of the everyday mechanics that allow the elephant to eat and drink and breathe and bathe—a tenderness which also reflects, through the mysterious symmetry of harmonic forms, the enduring partnership of Tatiana de Schlözer, Alexander Scriabin, and the music whose presence added so much meaning to their love.

“When on land,” Harrison remarks in his final words about the elephant, “he can dash water, sand, and mud all over his body, so as to cool and refresh the surface, and remove any source of irritation. Finally, by this instrument he can modify his voice, and increase its tone, so as to cause it to be heard at a distance of one or two miles, and, according to some, still more. Through it he can send forth trumpet sounds, loud, harsh, and discordant, but varying according as they are indicative of social or sexual feeling, or of terror, anger, or satisfaction.”