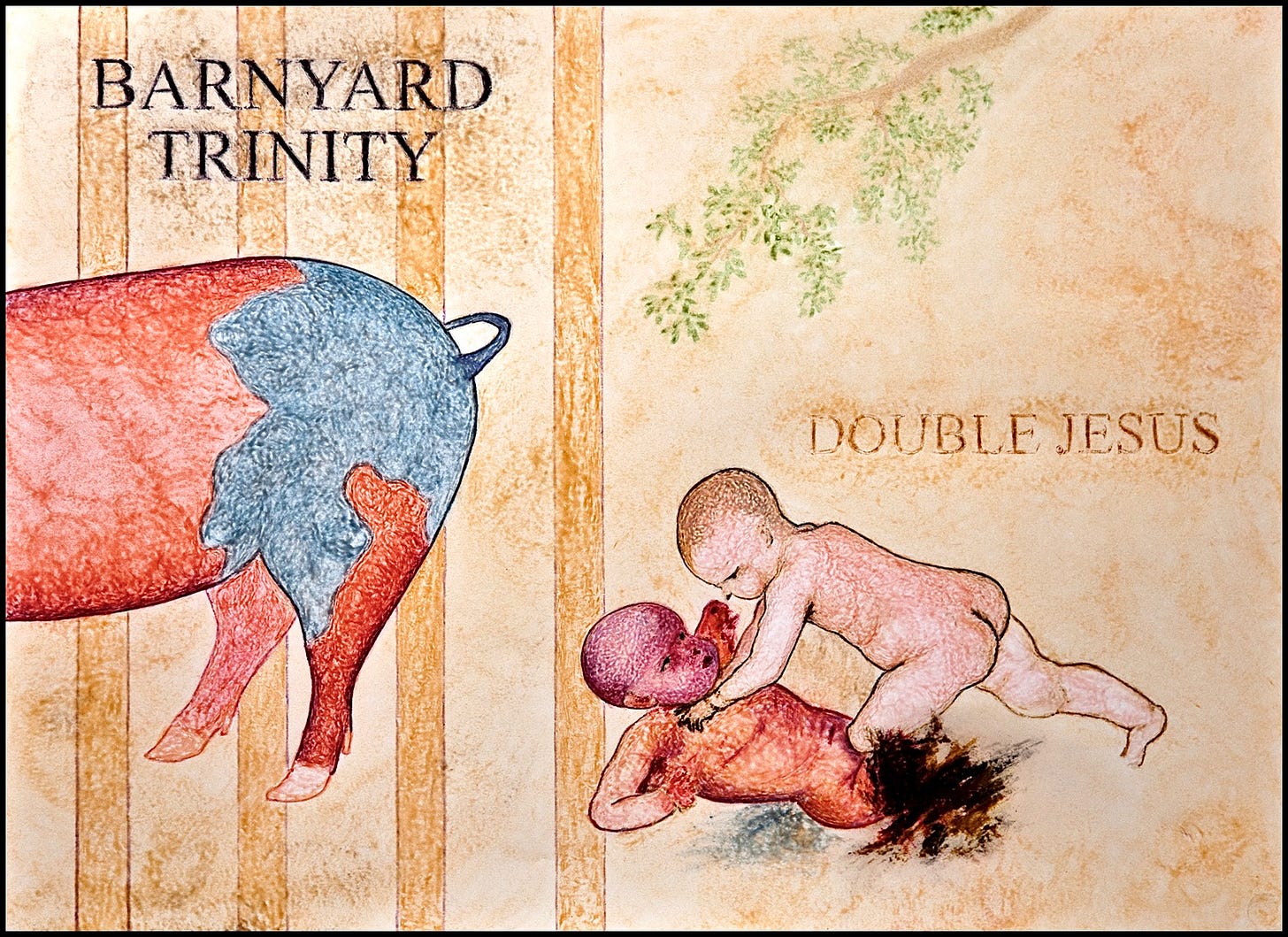

Barnyard Trinity

Scribbled by Atticus Bergman using Crayola crayons | 22”x30” | 2021

Barnyard Trinity

As far as theological principles go, the dogma of the Holy Trinity is complex, enigmatic, and wildly perverse.

It’s also extremely dramatic. Even though, on an architectural level, the Trinity is fashioned from a triple helix of confounding logic, once that helix is unfolded, its dense inner substance reveals an outrageous story of lurid, psychosexual intrigue.

In more philosophical terms, the Holy Trinity illustrates how ecclesiastical discourse perceives the scope of mortal life—or at least how Christian ideology situates the boundaries of human finitude in relation to a deity that, by definition, transcends all limits.

To do this, the doctrine describes the essence of God as a compound structure comprised of three separate characters. Each character exemplifies a different aspect of a larger totality. The first is responsible for having created life, and is therefore known as God the Father. The second is responsible for having briefly erased the distance between God and his creation, and is therefore known as God the Son. The third is responsible for animating the elements of world with the breath of divinity and is therefore known as the Holy Spirit.

Caught between the rays of this prism is Mary, the so-called mother of God. According to the standard biblical narrative, when Mary gave birth to Jesus Christ, she established herself as a conduit between the twin spheres of divinity and humanity. Through her influence, Jesus—otherwise known as God the Son—was stripped of his divine abstraction and incarnated on Earth as a mortal being. For Christianity as a whole, this moment was sufficiently important to define the religion and give it its name: a name inspired by Christ, rather than God the Father—a name, in other words, which earns its significance, not from the power of God, but from the anomalous moment when God chose to forsake that power and split himself into thirds.

Given that the same being which conspired to produce her child also, in fact, was her child, Mary occupies a position of curious intimacy in the story of her own maternal life—an intimacy which, by almost any measure, teeters on the edge of scandal and disgrace. Even Saint Augustine seemed to think that Mary’s arrangement was a little odd, observing that, in accordance with the logic of the Trinity, Jesus Christ was not only Mary’s son, but also her “infant spouse,” who was conceived in the “bridal chamber” of his mother’s womb.

Needless to say, this relationship set the tone for an unusually adventurous family dynamic. And yet, Augustine’s larger point was that the incarnation of Jesus was not a passive act. Instead, it was a moment of remarkable volition in which the unborn child personally selected the vessel of his nativity and, in so doing, played an exceptionally aggressive role in the act of his own conception.

Unfortunately, the Syriac Infancy Gospel fails to describe what happened to the foreskin after it ended up in Mary’s hair

Eight days after he was born, Christ’s willfulness was once again on display when the infant decided to orchestrate his own circumcision—an event which was so traumatic for his mother that it is often listed as the first of seven tragedies that define Mary as the Mater Dolorosa. Meanwhile, for the enterprising young child, the prospect of being butchered with a knife presented an exciting opportunity to test the physical reality of his flesh by suffering and bleeding—two of his favorite hobbies, which later defined his death and, in the process, became the abiding symbols of his Passion and his Church.

In a poem that was originally published in 1646, Richard Crashaw imagined a discussion in which Jesus—still only one week old—calmly identifies his circumcision as “the first fruits of my growing death.” In the minds of many Renaissance theologians, this statement expressed an important, literal truth about the temporality of Christ’s life: i.e. that the event of his death was already inscribed in the miracle of his birth. For them, Christ’s existence was not a linear progression from youth to maturity. Instead, it was a single instant of layered incarnation, whose implications spread outward in time like a seismic wave.

By compressing Christ’s biography into a single package comprised of three coterminous parts (birth, death, and resurrection), this formulation of biblical chronology replicates the structure of the Trinity. Moreover, it also poses the fascinating question of what, exactly, happened to Christ’s severed foreskin—a feature of his anatomy which was evidently included with his body when he was born, but was missing when he died, thereby disturbing the notion of Christ’s inviolable totality.

One opinion was that the foreskin ascended to Heaven with the rest of Christ, irrespective of its location at the time, let alone its state of morbid decomposition. A second opinion claimed that Mary Magdalene somehow managed to acquire Christ’s foreskin for herself. In this rendition of the story, which is included in the apocryphal text of the Syriac Infancy Gospel, the foreskin had already been preserved in oil and stored in an alabaster box, where it remained until Mary decided—for enigmatic reasons of her own—to dump the contents of the box on Christ’s feet. Then she bent over and mopped up the mess with her hair.

Unfortunately, the Syriac Infancy Gospel fails to describe what happened to the foreskin after it ended up in Mary’s hair—an omission which forced the 17th century Vatican librarian Leo Allatius to speculate that, after Christ’s death, it had risen into space, where its wrinkles were stretched in every direction until, eventually, the supple flap was transformed into the rings of Saturn. If nothing else, this image captures the cosmic significance of the transaction that purportedly occurred when God’s purity was split like the atom—a moment of fission which began with a partial renunciation of immortality, and ended with an explosion so large that it launched bits of debris through five layers of atmospheric gasses, across a billion miles of frigid darkness, and into the orbit of a planet that can barely be seen by the naked eye.

Even Saint Augustine seemed to think that Mary’s arrangement was a little odd, observing that, in accordance with the logic of the Trinity, Jesus Christ was not only Mary’s son, but also her “infant spouse”

In 1933, Alfred Adler proposed that Christianity enriches the moral imagination of society by placing the messiness of lived experience in dialog with the image of a perfect, transcendental god. Unfortunately, this thesis fails to account for the actual teachings of the religion, which insist that God went out of his way to participate in the ambivalence of human frailty rather than preserve his status as an unattainable ideal—an inversion of authority which conveniently flatters the constituents of the Church by suggesting that God’s greatest act was to become one of them.

Regardless of its suspicious practicality, this inversion represents a common social motif whose implications extend beyond the confines of the Trinity. In fact, a number of similar reversals took place in Adler’s own career as a psychoanalyst: for example in 1905, when Sigmund Freud complimented Adler on his “rare ability to put himself in the place of the ill person.”

By 1905, Freud had been friendly with Adler for about three years. Furthermore, he had arranged for him to become his brother’s doctor. In short, it was becoming apparent that Freud viewed the young psychologist as one of his most promising disciples. The only problem was that Adler didn’t share this view himself. For him, Freud was a colleague, not a master.

As a result, Freud diagnosed Adler as being insufficiently obedient—a dangerous symptom, which implied the possibility of delusional ambition or, even worse, rebellious paranoia. Before long, he was counseling his friends to handle Adler with “psychiatric caution.”

In the fall of 1911, one of Freud’s colleagues pressured Adler to publicly admit that he was “a Judas,” employing a slur whose ecclesiastical subtext would later become explicit in the memoirs of Max Graf when he observed that “Freud—as the head of a church—banished Adler; he ejected him from the official church.”

Outside the politics of Viennese society, Graf’s ecclesiastical language was echoed in the popular imagination of Europe, where psychoanalysis had installed itself as a secular reflection of Christianity. Not only was it a tool for understanding the intricacies of human suffering, it was also a symbol of power, authority, and omniscience. Psychotherapy didn’t just change people’s behavior; it did so through the use of mind-control and hypnosis.

Meanwhile, as the self-appointed father of this new church, Freud was in a unique position to reproduce the riotous, filial myth of the Trinity. And yet, in the end, he settled for merely reproducing its grandiose hierarchy, seeking shelter behind the more legible myth of Oedipus, while also labeling Adler as a renegade product of his own creation. As far as he was concerned, Adler was not a true rival. Instead, he was an insignificant blister that Freud had mistakenly allowed to swell.

Or as Freud himself phrased it: “I have made a pygmy great.”